I am not the biggest Shakespeare fan. I think I understand his charms as a poet, but the poetry doesn't translate well to stage, for me. I find many of the words too obscure to process quickly, so while I'm puzzling out what a line means, three more have gone by. For me, seeing one of Shakespeare's plays is doing battle with sometimes impenetrable language. So much of the meaning has to come through the actors--when I don't understand a word, or a phrase, or even an entire paragraph of dialogue, I have to rely on body language, gesture, and blocking to help me understand what's going on. Obviously, those things are always a part of communication, and in every play the way characters act clues you in to the meaning of their dialogue. But when I hear Shakespeare, the meaning the actors imbue to a line with their acting is often completely divorced from the words themselves, because I have no idea what the words mean.

I went to Romeo and Juliet at Cal Shakes on Saturday night.

The production was great. I loved the cast, especially Juliet and Mercutio. The two of them blew me away with energy and wit, which fit the production's aesthetic perfectly. The scenes and the characters felt important and vital, and the set design (minimalist) coupled with the costuming (generally simple, modern garb) focused attention on the acting. That worked, because the acting was great. The play itself was not what I expected.

I had not seen Romeo and Juliet before, and knew about the play only what I'd picked up through high school and cultural osmosis (the outline of the plot, several famous phrases). The thing that struck me about the play was just how young its central characters are. In the CalShakes production, Mercutio and Benvolio dial up the crass action pretty high (at one point, Mercutio moons the audience), and their characters are certainly written as some crude dudes. Juliet can hardly stop thinking about sex long enough to fall in love with Romeo. Romeo falls in love with Juliet after spending the first scenes of the play crippled by love for another girl. All these characters are children, which--to me--was the great tragedy of the play. The tragedy was not that Romeo and Juliet, star-crossed lovers, could not be together. The tragedy was that none of the adults in the play payed enough attention to the children to prevent them from making some very stupid decisions. I left wondering why these children felt they had to kill themselves for love.

Is the love between Romeo and Juliet "true" love? What does that even mean? Romeo is obviously infatuated with Juliet, and Juliet with Romeo. They pledge love to each other, then decide to marry less than 24 hours after meeting, mostly, it seems, so that they can have sex without pissing off God (or a devout audience?). What are their parents doing????

To return to my first paragraph, complaining about obscure language: the language doesn't just obscure the immediate meaning of words, but also Romeo and Juliet's youth. Their language--measured, careful, beautiful, mature--connotes a capability for serious thought which I doubt Romeo or Juliet could really have at their age. It leads us to trust their judgment more than if they spoke in uncertain sentences broken with awkward pauses as they picked at pimple scabs on their foreheads.

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Thursday, July 18, 2013

A few scattered thoughts from the last few days

I flew back to San Diego from New York yesterday, and tomorrow I leave for San Francisco. Tomorrow's my birthday. A week and a day from tomorrow is my wedding. Things are speeding up. Here are a few assorted links, and thoughts, from the last few days.

1) I watched Retreat, starring Cilian Murphy, Thandie Newton, and Jamie Bell, a few nights ago. It was a disaster, and I wouldn't recommend it, but it had a good premise: a couple (Murphy and Newton), their marriage foundering, take a vacation to save their relationship on an isolated island on which they are the only people. After a few days on the island, an unknown, wounded man (Bell) turns up. He tells the couple that a global pandemic has hit, and everyone on the mainland is infected. Their only chance is to board up the house and refuse entry to anyone finding a way to the island. The couple distrusts him, which makes some amount of sense, given that his story is fantastic and the couple can't even trust each other. The movie had the chance to have its theme (distrust and poor communication in marriage is toxic) align perfectly with its larger story, but it overthought itself. Retreat could have ended with the stranger's story proved true just as the couple's distrust consumes them all, so the audience can see how the couple's personal flaws doomed them. This would make something of a classical tragedy. Instead, the film provides a twist ending, in which the stranger has been lying the entire time, but the truth is much less plausible than the lie. The plot and thematic resonance is destroyed, and the movie is ruined. Blech. The lesson? Twists suck.

2) On the plane home I read "How Junk Food Can End Obesity," the cover story in this month's Atlantic. The piece suggests that the obesity epidemic is much more likely to be solved by reducing the calorie counts of McDonald's sandwiches (and other junk food items) than by anything else. Instead of expecting people to change where and how they eat, the author thinks it much more practical to make minor, calorie-conscious changes to what people are always going to eat. This strikes me as, well, sorta plausible, and not a bad idea. It doesn't require any major cultural shift to achieve, even on the part of fast food restaurants. The author already reports on some of lower-calorie options (which are still savory, meaty, cheesy, and sometimes eggy) that McDonald's already offers. But none of the suggestions are actually about nutrition, although the article expends many words talking about nutrition. The suggestions are simply about scale. Less calories means less obese people. Unhealthy people who are not obese are beyond the scope of the article.

3) I read an item in New York magazine about "The Boxer at Rest," the sculpture currently on display at the Met. The boxer is, above all, vulnerable. He's wounded; he's suffered cuts and bruises in the fight, yes, but his body also bears the marks and wounds of his occupation. He has cauliflower ears, a smashed nose, and his foreskin has been sewed shut. The sculpture fits right into a contemporary conversation about sports (especially violent sports) and exploitation. The boxer has suffered wounds and mutilations for his sport. In the moment captured here, after the fight, does he seem to believe it was worth it? It's rare to have a dialogue about sports entirely concerned with something other than the Big Game. Here, we see pain and vulnerability divorced from glory. It makes glory look different.

1) I watched Retreat, starring Cilian Murphy, Thandie Newton, and Jamie Bell, a few nights ago. It was a disaster, and I wouldn't recommend it, but it had a good premise: a couple (Murphy and Newton), their marriage foundering, take a vacation to save their relationship on an isolated island on which they are the only people. After a few days on the island, an unknown, wounded man (Bell) turns up. He tells the couple that a global pandemic has hit, and everyone on the mainland is infected. Their only chance is to board up the house and refuse entry to anyone finding a way to the island. The couple distrusts him, which makes some amount of sense, given that his story is fantastic and the couple can't even trust each other. The movie had the chance to have its theme (distrust and poor communication in marriage is toxic) align perfectly with its larger story, but it overthought itself. Retreat could have ended with the stranger's story proved true just as the couple's distrust consumes them all, so the audience can see how the couple's personal flaws doomed them. This would make something of a classical tragedy. Instead, the film provides a twist ending, in which the stranger has been lying the entire time, but the truth is much less plausible than the lie. The plot and thematic resonance is destroyed, and the movie is ruined. Blech. The lesson? Twists suck.

2) On the plane home I read "How Junk Food Can End Obesity," the cover story in this month's Atlantic. The piece suggests that the obesity epidemic is much more likely to be solved by reducing the calorie counts of McDonald's sandwiches (and other junk food items) than by anything else. Instead of expecting people to change where and how they eat, the author thinks it much more practical to make minor, calorie-conscious changes to what people are always going to eat. This strikes me as, well, sorta plausible, and not a bad idea. It doesn't require any major cultural shift to achieve, even on the part of fast food restaurants. The author already reports on some of lower-calorie options (which are still savory, meaty, cheesy, and sometimes eggy) that McDonald's already offers. But none of the suggestions are actually about nutrition, although the article expends many words talking about nutrition. The suggestions are simply about scale. Less calories means less obese people. Unhealthy people who are not obese are beyond the scope of the article.

3) I read an item in New York magazine about "The Boxer at Rest," the sculpture currently on display at the Met. The boxer is, above all, vulnerable. He's wounded; he's suffered cuts and bruises in the fight, yes, but his body also bears the marks and wounds of his occupation. He has cauliflower ears, a smashed nose, and his foreskin has been sewed shut. The sculpture fits right into a contemporary conversation about sports (especially violent sports) and exploitation. The boxer has suffered wounds and mutilations for his sport. In the moment captured here, after the fight, does he seem to believe it was worth it? It's rare to have a dialogue about sports entirely concerned with something other than the Big Game. Here, we see pain and vulnerability divorced from glory. It makes glory look different.

Monday, July 15, 2013

Hello, No Irony

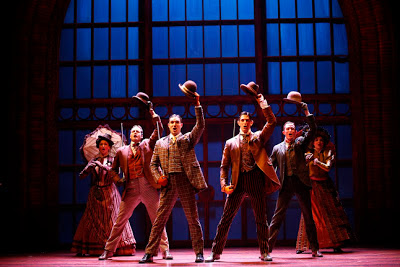

When I was in D.C., about three months ago, I went to see Hello Dolly at Ford's Theater. I like musical theater, though I'd never seen Hello Dolly before. It was jarring. The musical was first produced on Broadway in 1964, and the story is set around the turn of the 20th century. The society portrayed in the show is not modern--it reflects the prejudices of the time the show was written--and the show is a comedy, whose premise and jokes are generally anti-feminist. That the show was anti-feminist is not particularly interesting--I imagine that Hello Dolly isn't much worse on that score than the rest of America's pop-cultural output in 1964. But it's not 1964 anymore.

The production at Ford's presented the show without irony, or cynicism. The laugh lines were delivered as written, told without comment from the director or actors: punchlines were directed at women, instead of at those who would seek to curtail women's freedom. Watching the play was strange, as though I had been transported to 1964, when these jokes were funny (most of the crowd was laughing along. The actors sold the jokes well.).

I get why the show might still be produced in 2013: the music. People love the music. And the music is good, I guess. But does a modern production need to mimic the historical context of the original production just to showcase its music?

Performing Hello Dolly might always be problematic, no matter what sort of direction is given. But a healthy dose of irony couldn't hurt. It was deeply strange to be audience to a show unabashedly asking me to laugh at jokes with women as the punchline. With irony, the punchlines might sound different, and the object of all those problematic jokes might change enough to make them palatable. This, of course, means modernizing the show. It means updating the show to appeal to a modern audience, and changing the way the play comes across--contravening the intent of its authors. Doing this adds a directorial meta-comment about the show's worldview.

I love history and, in a sense, what I saw was history. I saw a production as it might have been given in 1964--a sort of reenactment of a musical in an earlier time. But why? Reproducing Hello Dolly this way is sort of like remaking any movie from 1964 shot-for-shot and line-by-line. Why do that?

The production, otherwise, was mostly good--great acting, awesome costuming, though there were a few moments of incoherent blocking near the end. Still, despite the quality of the production, I'm not sure why it was done. Was the music and the costuming enough to justify a production selling retrograde society?

Friday, July 12, 2013

This is it

This is it: the beginning of a month of traveling. First a bachelor party in New York, then a few weeks in San Francisco for my wedding (!), then a slow, week long drive up the coast before stopping at Portland for another wedding.

I don't intent to neglect the blog. I've got some posts queued, and I'll find time in the coming weeks to write some stuff about marriage and the wedding, I'm sure. For today, I'll just say: I'm excited. I'm excited to travel, excited to see family and friends, excited to celebrate my wedding, and, most of all, I'm excited to be married. I feel very lucky to have my partner.

A note on the programming: I'm going to post regularly on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday every week. (Unless I don't feel like it.) So, see you Monday. Here's a cat picture.

I don't intent to neglect the blog. I've got some posts queued, and I'll find time in the coming weeks to write some stuff about marriage and the wedding, I'm sure. For today, I'll just say: I'm excited. I'm excited to travel, excited to see family and friends, excited to celebrate my wedding, and, most of all, I'm excited to be married. I feel very lucky to have my partner.

A note on the programming: I'm going to post regularly on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday every week. (Unless I don't feel like it.) So, see you Monday. Here's a cat picture.

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Calvary

I'm working on an essay about Calvary Cemetery of San Diego. I won't say too much about it yet, except that I'll have a lot to say about it later. For now, a brief item. I've found a lot of great data that I couldn't help sharing here.

The first burial at Calvary, a Catholic cemetery located in what is now the Mission Hills neighborhood (just a few blocks from my place), was in 1873. The last burial was in 1960. Above is the graph of burials vs. time*, which shows increasing use of Calvary until 1918, followed by a precipitous decline in new interments. Calvary's story is about decline, neglect, decay, and forgetting. The decline is right there in the graph. To know that there was neglect, you need the above data and the knowledge that Calvary had no endowment for perpetual care. Decay followed neglect; forgetting followed decay. The cemetery was converted into a public park in 1970.

That the cemetery was converted into a park is not necessarily evidence of forgetting. Today, the park contains a few headstones from the old cemetery, and a small memorial to those interred within the park. The story of how the cemetery became a park, however, is not pretty, and has been willfully forgotten.

Ok. That's my Calvary teaser. I'll post more about the cemetery in the coming weeks.

*Data collated from the rootsweb online database dedicated to Calvary burials, which can be found by clicking here. The total number of burials recorded in the graph is 4,001, though I don't know whether the database is comprehensive. Certainly, the trend of the graph reflects the qualitative analysis I'd found from many sources. For years before 1884, and after 1918, the graphed data reflects all Calvary burials recorded in the database. For the period 1884-1918, I'd estimate uncertainty up to 5% in the graphed burial values.

Monday, July 8, 2013

A quick thought on American middle-class individualism

I finished A Storm of Swords a few days ago. Yeesh. It's nuts. Emily and I have plans to read the last two books together, which will slow them down considerably, reducing the amount of time we will have no new A Song of Ice and Fire content to consume, a consumption which has become something of a compulsion. This means I have time to read something else when I read on my own. I've started West from Appomattox, Heather Cox Richardson's history of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. I haven't read much, but was struck by a passage in the introduction about the rise of an American middle-class after the Civil War:

Middle-class ideology was both the greatest triumph and the greatest tragedy of reconstruction. It was an astonishingly inclusive way to run a country, making certain former slaves and impoverished immigrants welcomed participants in middle-class America, offering to them opportunities they could not have imagined in other countries, and it advanced women's position in a dramatically short time. But this ideology also rendered Americans unable to recognize systematic inequalities in American society. Anyone who embraced the mainstream vision came to believe he or she was on the road to a middle-class life, no matter what the reality of his or her position actually was. When things went wrong, individuals had no one but themselves to blame for failure, even if its causes lay outside their control. A man unemployed during a recession or a woman beaten by her husband could find little sympathy in the middle-class worldview. More strikingly, though, this mindset deliberately repressed anyone who called for government action to level the American economic, social, or political playing field. If a group as a whole came to be perceived as looking for government handouts its members were aggressively prohibited from participating equally in American society, and all of the self-help in the world wasn't going to change that.I think this is a really well-observed interpretation of the way a normative class justifies its own privilege without necessarily recognizing that its privilege exists. She continues:

The powerful new American identity permitted many individuals to succeed far beyond what they might have achieved elsewhere, but that exceptional openness depended on class, gender, and racial bias.And that's the rub. The inconsistency in what Richardson calls the "middle-class ideology"--complete individual responsibility coupled with a desire for increased federal involvement in everyday life--was only possible because it had a scapegoat. If it wasn't for Those Other People, everything would be perfect. Therefore, all problems could be blamed on Them, a strategy that enables Us to move forward without considering Our own complicity in said problems. If this sounds familiar and contemporary, that's because it is, and Richardson knows this. Her interpretation holds that the America made during Reconstruction is the one we inherited.

I tend to agree with that interpretation, insofar as the story of modern America cannot be told without an explanation of Reconstruction's various ambitions and failings, but I'm interested in how she goes about proving it.

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

Why I stopped eating meat

I've always considered meat an essential part of my diet, and meat-eating an important part of who I am. I have a great carnitas recipe, l love beef stew, and I have lots of opinions about hamburgers. For years, I scarcely went a day without meat in my diet. I learned to cook making meat dishes, and wooed my partner cooking meat. Meat is, and has always been, important to me.

And yet: I'm a vegetarian.

A few months ago, I changed my diet. Due to my aforementioned affinity for meat, I was eating too much of it. I decided to scale back my meat consumption. I didn't do this to remedy any acute health concerns--the choice was more about avoiding acute health concerns in the future. I made a rule: no meat during the week. During the week, I ate vegetarian. On the weekends, I ate what I liked. The rule worked, and I ate much less meat as a weekday vegetarian. That was good.

As I managed my cravings and held out for the weekend, I began to wonder if I should eat meat at all. Meat had always been a huge part of my diet. Then, it wasn't, and I felt about the same. Most of the time, my body felt better without meat. After a month or two, I still ate meat, but I no longer considered myself a meat-eater; that wasn't an important part of "me", anymore. For the first time, I questioned my decision to eat meat.

Scrutinizing my choice to eat meat was humiliating, in a way, because I confronted an unseemly lack of self-awareness about my eating habits, and a much broader lack of awareness about the consequences of my food choices. Food is such an important part of any life, and an especially important part of mine, but I had never thought about the ethics of eating before. I had, until recently, ignored them--willfully so. Almost immediately, upon serious consideration of my eating habits, I realized that--for me--meat-eating was completely indefensible. The argument for this is very simple--humiliatingly simple:

(1) Animals are alive, know they're alive, and want to be alive.

(2) Any being satisfying criteria (1) has a right to life--just as I have a right to mine.

If other beings have a right to life, it is wrong to kill them just to eat them. A caveat: if I could not feed myself, for whatever reason, except with meat, I would do it. I don't believe that an animal's life is more important than mine, but this is more than killing an animal for the pleasure of eating it--it's killing an animal to live. In that case, killing an animal for food is justified, but I've always eaten meat for pleasure, not necessity. I've always been able to feed myself without eating meat, though I've never eaten vegetarian until now. When I consider the reason behind my desire to eat meat--meat tastes good--against the death that made my meat-eating possible, my reason stands out as terrible: frivolous, capricious, and cruel.

I haven't made mention of the suffering of farmed and slaughtered animals, though this is another reason to avoid meat (especially factory farmed meat). Animal suffering is another horrible consequence of a frivolous choice. Meat tastes good. But is that reason enough to torture and kill animals? Any arguments which answer "yes" resolve to the same thing: power justifies itself. Because animals are weak, and we can eat them, eating them is not wrong. This sort of argument, which is not an argument at all, is not just profoundly unsatisfying. It's dangerous. I'm thinking of all arguments of the same ilk which, historically, have been used to justify the exploitation of the vulnerable or weak--few have held up well over time.

I realize that this is radical. For someone who believes that animals do not have a right to live, none of what I've argued makes any sense. However, I would urge anyone who cares about their food, and who chooses to eat meat, to scrutinize that choice. For me, it was difficult, but worth it. In any case, it's good to think hard about eating, perhaps the most important (and most frequent) thing any of us ever do to affect our health and well-being.

And yet: I'm a vegetarian.

A few months ago, I changed my diet. Due to my aforementioned affinity for meat, I was eating too much of it. I decided to scale back my meat consumption. I didn't do this to remedy any acute health concerns--the choice was more about avoiding acute health concerns in the future. I made a rule: no meat during the week. During the week, I ate vegetarian. On the weekends, I ate what I liked. The rule worked, and I ate much less meat as a weekday vegetarian. That was good.

As I managed my cravings and held out for the weekend, I began to wonder if I should eat meat at all. Meat had always been a huge part of my diet. Then, it wasn't, and I felt about the same. Most of the time, my body felt better without meat. After a month or two, I still ate meat, but I no longer considered myself a meat-eater; that wasn't an important part of "me", anymore. For the first time, I questioned my decision to eat meat.

Scrutinizing my choice to eat meat was humiliating, in a way, because I confronted an unseemly lack of self-awareness about my eating habits, and a much broader lack of awareness about the consequences of my food choices. Food is such an important part of any life, and an especially important part of mine, but I had never thought about the ethics of eating before. I had, until recently, ignored them--willfully so. Almost immediately, upon serious consideration of my eating habits, I realized that--for me--meat-eating was completely indefensible. The argument for this is very simple--humiliatingly simple:

(1) Animals are alive, know they're alive, and want to be alive.

(2) Any being satisfying criteria (1) has a right to life--just as I have a right to mine.

If other beings have a right to life, it is wrong to kill them just to eat them. A caveat: if I could not feed myself, for whatever reason, except with meat, I would do it. I don't believe that an animal's life is more important than mine, but this is more than killing an animal for the pleasure of eating it--it's killing an animal to live. In that case, killing an animal for food is justified, but I've always eaten meat for pleasure, not necessity. I've always been able to feed myself without eating meat, though I've never eaten vegetarian until now. When I consider the reason behind my desire to eat meat--meat tastes good--against the death that made my meat-eating possible, my reason stands out as terrible: frivolous, capricious, and cruel.

I haven't made mention of the suffering of farmed and slaughtered animals, though this is another reason to avoid meat (especially factory farmed meat). Animal suffering is another horrible consequence of a frivolous choice. Meat tastes good. But is that reason enough to torture and kill animals? Any arguments which answer "yes" resolve to the same thing: power justifies itself. Because animals are weak, and we can eat them, eating them is not wrong. This sort of argument, which is not an argument at all, is not just profoundly unsatisfying. It's dangerous. I'm thinking of all arguments of the same ilk which, historically, have been used to justify the exploitation of the vulnerable or weak--few have held up well over time.

I realize that this is radical. For someone who believes that animals do not have a right to live, none of what I've argued makes any sense. However, I would urge anyone who cares about their food, and who chooses to eat meat, to scrutinize that choice. For me, it was difficult, but worth it. In any case, it's good to think hard about eating, perhaps the most important (and most frequent) thing any of us ever do to affect our health and well-being.

Monday, July 1, 2013

What I read in June

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin. I love lore, which is one reason I love history. The primary challenge of history is to synthesize lore into a story about the past. Speculative fiction and history, I would argue, face some of the same challenges to achieve authenticity, but fiction can avoid lore if it wants to. History cannot. Fiction, like history, must establish historical context to tell a coherent story--without a sense of time and place, a reader can't understand the stakes for a protagonist--but history is built of lore, while fiction can get away with conjuring historical context from symbols, images, finely observed detail, and passing references. I'm thinking of something like Doctorow's The March, a work that conjures the atmosphere of the Carolinas of 1864 to tell its story, but features less information about the events of the march than you could find in a few minutes skimming Wikipedia.

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin. I love lore, which is one reason I love history. The primary challenge of history is to synthesize lore into a story about the past. Speculative fiction and history, I would argue, face some of the same challenges to achieve authenticity, but fiction can avoid lore if it wants to. History cannot. Fiction, like history, must establish historical context to tell a coherent story--without a sense of time and place, a reader can't understand the stakes for a protagonist--but history is built of lore, while fiction can get away with conjuring historical context from symbols, images, finely observed detail, and passing references. I'm thinking of something like Doctorow's The March, a work that conjures the atmosphere of the Carolinas of 1864 to tell its story, but features less information about the events of the march than you could find in a few minutes skimming Wikipedia.What does this have to do with A Game of Thrones? I decided to read the A Song of Ice and Fire novels after watching the first three seasons of the HBO adaptation, which frustrated me with its pointed lack of lore. The show conjures its historical context with imagery, atmosphere, and reluctant scenes of exposition, which, especially in the first season, tend to be very bad. A Game of Thrones has no end of lore. It's primary purpose, at times, is to deliver lore for lore's sake. The whole thing is a joyous gush of lore. The total lore I learned from reading the novel was vastly more than I learned in the first season of the show, and the lore per hour was greater as well. The whole thing was one long loregasm.

So it occurred to me, not long after beginning A Game of Thrones, that the novel (and the series) were one long history of Westeros. The histories of this world are told primarily through songs--its people are generally illiterate--and the series is called A Song of Ice and Fire. The first novel is the history of Ned Stark, the tragic, honorable Lord of Winterfell, and his family. To properly convey context, there is tons and tons of lore. It's great.

The story itself is quite gripping. One of the things I loved about the show, and enjoyed more in the books, was the handling of honor. Honor is valuable in Westeros, though not as valuable as shrewd practicality. The novel shows quite clearly how honor leads Ned Stark to destruction, endangering his family and bannermen. The novel shows that its characters care about honor, though many of them only pay it lip service. In Westeros, honor has value, but how much? That's one of the big questions of the novel.

A Clash of Kings by George R. R. Martin. The second novel of A Song of Ice and Fire, and no less chock full of lore than the first. The story seemed less focused than in A Game of Thrones. A few characters spend the whole book wandering around, pretty much: Arya wanders with Yoren, then with Gendry and Hot Pie, then stops for a breath in Harrenhall, then escapes to wander again; Daenerys wanders the Red Waste, then wanders in Qarth; Bran does nothing, and ends up wandering north to the wall with Rickon. But there's so much good in all these scenes of wandering. Through Arya's eyes we see the desolation and horror of war for smallfolk. As Daenerys wanders, she matures into a leader. With Bran--well, I'm not quite sure what Bran's good for. Warg lore?

A Clash of Kings by George R. R. Martin. The second novel of A Song of Ice and Fire, and no less chock full of lore than the first. The story seemed less focused than in A Game of Thrones. A few characters spend the whole book wandering around, pretty much: Arya wanders with Yoren, then with Gendry and Hot Pie, then stops for a breath in Harrenhall, then escapes to wander again; Daenerys wanders the Red Waste, then wanders in Qarth; Bran does nothing, and ends up wandering north to the wall with Rickon. But there's so much good in all these scenes of wandering. Through Arya's eyes we see the desolation and horror of war for smallfolk. As Daenerys wanders, she matures into a leader. With Bran--well, I'm not quite sure what Bran's good for. Warg lore?Though Sansa isn't my favorite character, her chapters became my favorites in this novel. In the first novel, Sansa believed in the existence of a world that never was: the world told in the songs, a just world of honor and beauty. After the execution of her father, she finally sees the world for what it is, but doesn't want to believe it. She still wants to believe in honor and beauty. Her chapters are haunted with the horror of realizing the world is much different than she thought it was, and much worse. Joffrey forcing Sansa to look at her father's head, spiked to the top of a wall of the Red Keep, was the most brutal thing to happen to any character in the whole book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)